|

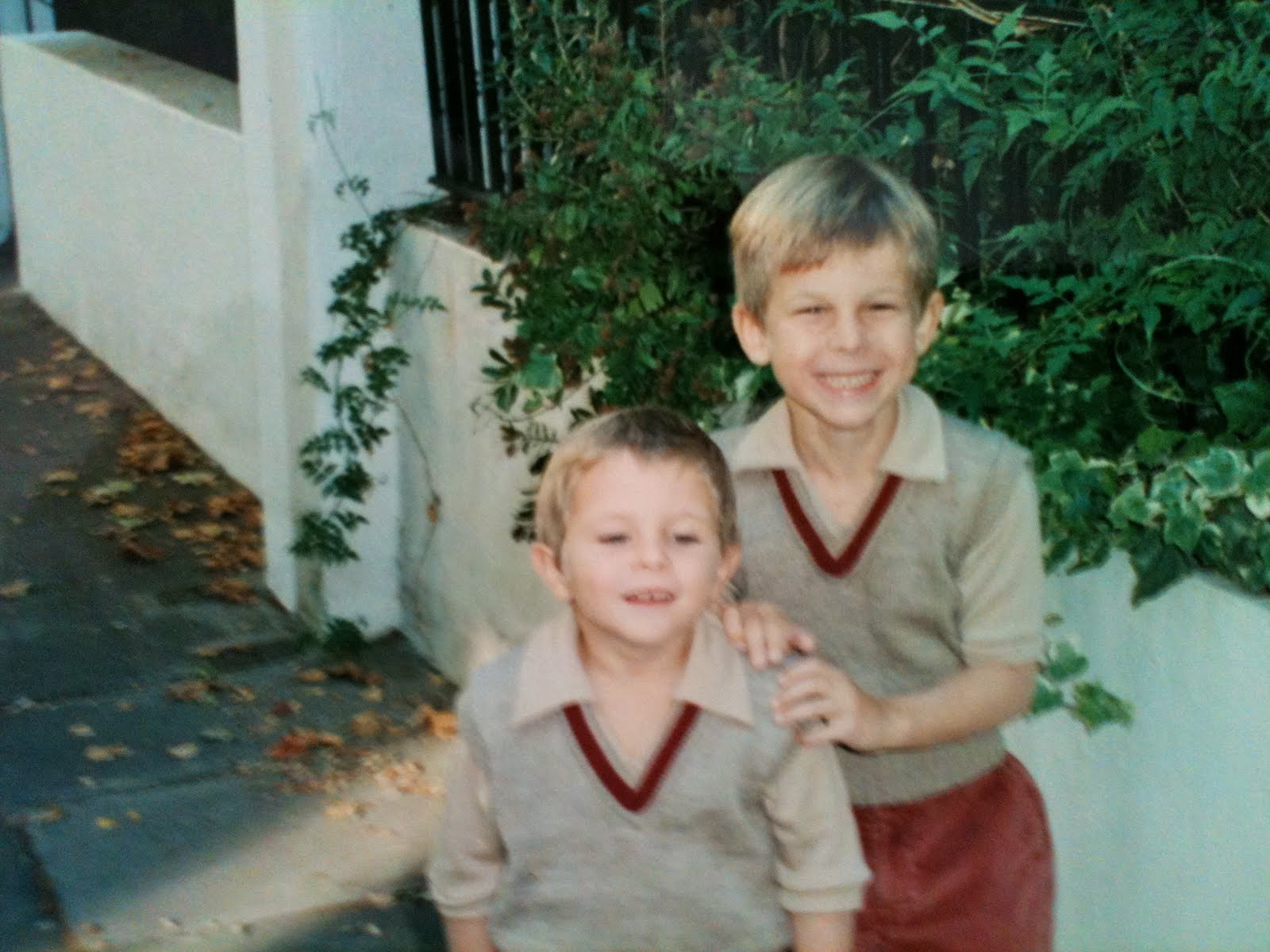

| James |

I am in a state of longing. Spring is such a near thing and yet, this morning, the little pot of ivy I left out is rimmed in frost. Frost! I rub salt into my homesick wound by checking the London weather on my computer dashboard: 75 all week. I squeeze lemon into my emotional paper cut by watching the Kings Road web cam obsessively. I can see the school children in their woolly jumpers and tidy lines serpentine along the footpath on their way between playing fields and classrooms. For a moment I am sure I see my own in that line. Perhaps it’s because my photographs of that time are so blurry?

So it is not just Spring in London I long for. It’s the Spring of my younger sons who, having spent the dark year in brown corduroy knickerbockers, were released into brown corduroy shorts each April. The promise I made them as we packed for Easter break was that when we came back it would be miraculously warm; every bulb up and in glorious bloom, the wisteria that twined so vigorously over the front of our house fully draped in pale green leaves and furry grape clusters of buds. And that was a promise I could keep, every year. I miss the reckless, headlong rush to the playground each afternoon that the sun was warm enough to sit on a park bench without icing over. The way James would walk through the gate with his head on a swivel looking for potential friends. “Hi, kids!” he’d call, confident that a game of pirates or hide and run was just around the corner. William, incandescent with delight, would run like mad to keep up, his legs a blurry pinwheel.

|

| William and his tooth |

I want the Spring back, the one when William went ass over teakettle on his tricycle, not once but twice. He didn’t cry, even though one front tooth stayed gray from the fall until it fell…out. Then there was Emma who was so Springy she fairly bounced. Her hair was so blond it was white and it would not grow. For years, until she was six at least, it stayed pixie short and although to me she was as feminine as a flower fairy, she was often mistaken for a boy. “Let the little boy go first,” a mother would say as Emma made a run on the slide, or “Why don’t you ask that nice boy to play?” from a nanny who had grown weary of her charge.

|

| Emmett |

My sons played tennis at a wonderfully raggedy but terribly posh tennis club when we lived in Wimbledon. Every Spring the club opened with little fanfare but enormous excitement for the players. It was another marker that the seasons had, at last, changed. Because it was Wimbledon, there were two grass courts along with the regular ones. There was always a bun fight to see who got to play on them. During the Wimbledon Fortnight we might even see a real player practicing. Emma was a toddler and while the boys took their lesson and rallied with other members, she and I would play enthusiastic catch with each other. The club manager and head instructor was a robust young Dutch woman. She was six feet tall and her cheeks were rosier than Emma’s. She had the perfect temperament for her job: game, energetic and jolly. She strolled the club watching, offering tips and encouragement in her sharp, slightly guttural accent. She loved to frolic with Emma and was absolutely convinced that she was a boy. If Emma was wearing pink (something she did infrequently as she inherited all her brothers’ clothes) the manager might give her a curious look before she walked away, but no more.

I let this go on for as long as I could, hoping she’d hear James or William talking to their sister and “get it.” It was just too awkward to correct her after the tenth time she said “What a cute boy, you are! You’ll be out there on the court with your brothers in no time.” Finally I made my move. “Come, Emma,” I said loudly, with a big smile at Famke Van Heusen (or Van Rijn or Vermeer, I can’t remember). “Oh!,” Famke said and I thought, ah, at last she’ll know that Emma is a girl and I won’t have had to embarrass her directly. “Oh!” she repeated, “Yes, let’s get your brothers, Emmett.” Emmett? To this day the boys will call her Emmett with great affection.

|

| Peony-to-be |

But I am lost again. It seems that I am longing for more than Spring, then. With a sensation very like hunger I serve myself these memories. Still, I pine for something now, present in this minute; the recollection of seasons past is hardly satisfying, the possibility of Spring is not enough. I lean, like the peonies outside my door, toward something to feed me, to push me forward in my day. But, unlike those peonies I am stunningly unproductive. Even now I hear the buzz of the washing machine, I scowl at the stack of bank statements, the line of unread emails and I just can’t move. In this season of almost sensual growth I am curiously languid. And then I see why.

I am not about Spring anymore. My Spring is past, my Summer more than halfway over. My children do not ask when they can wear short sleeves anymore, they don’t want to know how many months until they can go strawberry-picking in the South Downs. Two of them would no longer eat a strawberry if you held a bowl of whipped cream to their heads. Today, the youngest left me with a half wave and the most reluctant of “I love you’s.” Her hair is long at last, her legs longer and her neck is as gracefully curved as a swan’s. There is no mistaking Emma for Emmet anymore.

All this makes me incredibly proud, this growth that has sent my three shooting out of their home soil into the sun. And it makes me ineffably sad. There is almost nothing I can feed them now, not really. They are capable, able, strong, just as I prayed they would be. And yet, all I want is questions, tears, weakness. All I desire is to hold them close, each of them; to be the only one who can find the shorts, the pinnies, the sandals. I am terribly selfish, but I can’t help it. I still want to be the only one who can promise them Spring.