My mother would be so proud. Oh, not that her first grandchild, the only one she ever knew, and then only for a year, has just graduated from college. That’s a given.

Nor that I now have a garden the is full to bursting with dahlias and delphinium, salvia, Russian sage, roses and cheery daisies. She’d expect no less. And, not even that my lettuces are tender, my arugula bitter and crisp, my basil as fresh and aromatic as summer itself. No, my mother would be positively incandescent with joy that I inherited her ‘clandestine pruning’ habit. That is to say that when I see roses draped over a footpath or lilacs poking through a fence, peonies lonely in an unkempt front yard, I am compelled to snip away. We used to scream and yell at my mother when she did that, when she pulled over to the side of a deserted East Hampton road to dig up a fern, or cut a particularly beautiful low hanging branch of dogwood.

She might even dart across the empty railroad tracks to get at a neon bright forsythia bush. And when we yapped and spluttered that these were not her flowers, not her garden, and what the heck was wrong with her, Mommy just said, “Listen, it is essential to prune. These people would thank me if they knew that I am saving them from their own careless natures”. Right after they chase you away with a pitchfork.

We could not, could not understand what the hell she was doing. We had our own garden full of zinnias and tart marigolds, rhododendron and azalea, herbs and impatiens, tomatoes and zucchini. Still, she wouldn’t leave the house without her secateurs hidden in the glove box or shoved into the pocket of her khakis. It was a mystery to me, this drive to bring the outside in. I didn’t yet get that swift intake of breath that happens when the rosey/not rosey fragrance of peonies overtakes you. I didn’t appreciate the intense, gritty pleasure of hammering the woody stems of hydrangea so that the green flashes beneath the bark, the satisfaction of the cloud of purple and blue hovering above a simple white bucket. There was no way I could comprehend the need to fill a house with flowers, not then anyway.

I finally got it about fifteen years ago; that need to be covered with dew and dirt and petals. In those days the boys played cricket on a beautiful pitch not far from our Wimbledon house. I was always a bit early to collect them at the end of practice because I liked to watch the splash of their white kit against the grass, the blur of the red ball as it whizzed out of a bowler’s hand. On one of those afternoons I noticed a huge stand of lilacs set back behind a tangle of brambles. Oh my God, I thought, no one cares about those, I could just fill my arms with blossoms. And that’s what I did, the next morning. I pulled on Wellies and waded through the thorns until my secateurs could reach the lilacs. The scent was so heavy I could feel it in my mouth. I not only filled my arms, I filled the back of the Land Rover. My hands and wrists were laced with scratches, blood beading in a seam along each one. I didn’t even notice. When I got home I covered the table with every container I had: Ironstone pitchers, glass vases, jam jars, bud vases, a pint milk bottle from my front stoop. I spread out newspaper and thumped away at the stems until I knew they were split enough to take up water.

Later, back in central London I discovered a wall, easily thirty feet long, covered with climbing roses in a pink so pale they were nearly white. I plucked and snipped to fill teacups (their stems were short) and tiny milk jugs and placed them at my bedside. Even in my dreams the scent was clear as water. I took to packing my secateurs in my shopping trolley, in my glove box so that, should I see a deep magenta peony bush–unloved, untended– within (semi) easy reach, I might bring it home. Now, Emma cringed at my side as I leaned over a pointy iron fence to get a perfect cluster of muscat in the shade. Now she was hissing at me as I balanced precariously on the running board of the car so I could reach the white lilacs hanging over the Edwards Square fence. She warned that the gardeners were advancing on me, fixing us both with a gimlet eye as I gunned the engine and shouted at Emma, “Get in, get in, save yourself!”

One early summer I sent David to cut some peonies I saw sitting in lonely splendor outside the abandoned club house beside that cricket pitch. He returned in a fury; that clubhouse was not abandoned and when he bent to cut the peonies, the owner dashed out to confront him. When I tell you he ran for his life, I mean it. Never, never threaten an Englishman’s flowers.

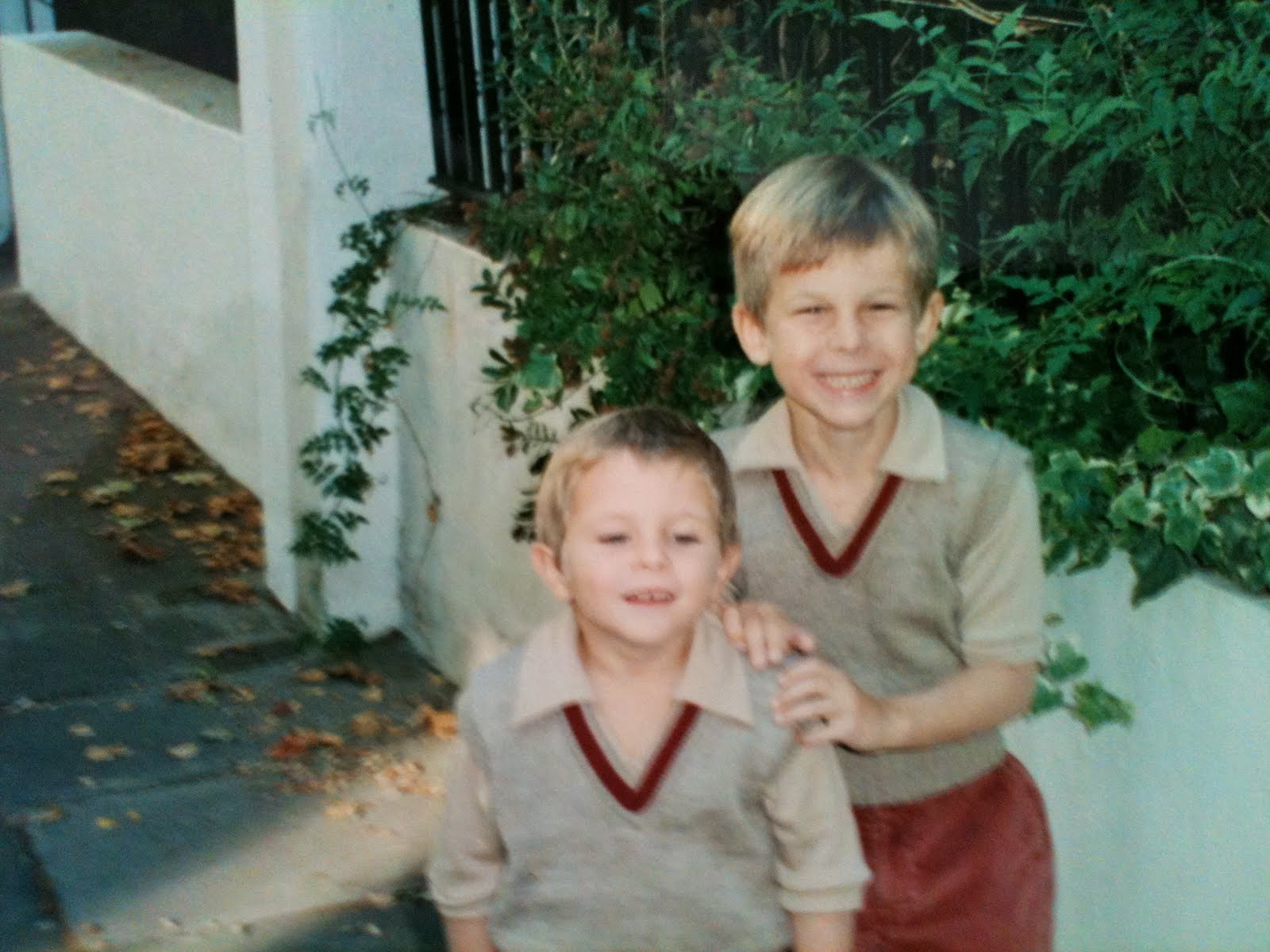

I can hear you, screaming and yelling at me now, “What the hell are you doing?” Or more to the point, “Where the hell are you going?” Not sure, so I won’t blame you if you click away and save yourselves. Only, there’s this: when I still did the school run every day, collecting three children of varying sizes and temperaments, I would joke that I was “gathering my rosebuds, while I may.”

Now, of course, my rosebuds are blooming; they have no need of my careful arrangement. And no matter how regularly I pack my gardening implements when I go out and about, there is not quite so much to gather anymore, and no one to shriek at me as I reach for a rose or sneak up on an unsuspecting Bridal Veil, no one to watch me strip away dead leaves, neatly clip sharp thorns, mix a bit of sugar into the water and set my jars, glasses, vases and pitchers on the table. But, that’s okay, I think, because a couple of weeks ago, when James graduated from college, everyone was there: the siblings and parents and grandparents. Every rose was gathered around and for a weekend, at least, we were a bouquet again. I am not, it seems, a careless gardener at all.